Throughout the centuries and around the world, book banning has been in place to some degree – in Europe during the Renaissance, in Nazi Germany during the 1930s and 40s, and most recently, in modern America. With the rise of banned books today comes an increase in controversy as teachers, librarians and students question whether this is truly beneficial, or just a method of pushing a conservative agenda.

But it’s important to establish some context first. Much of the younger generation has only recently heard about book banning for the first time, myself included, in the wake of the spike in the early 2020s. However, book bans have been around since nearly the invention of books themselves.

In the 1400s, Johannes Gutenberg of Germany invented the first mechanized printing press, changing the spread of information forever. Printed materials were able to be manufactured more efficiently than ever before, allowing members of the common class to acquire reading material more easily. With this came the spread of knowledge that previous generations had never encountered, as formal education back then was a luxury only the upper classes could afford.

There were many more reasons that the printing press was revolutionary. This spread of information led to more people understanding the world around them, giving less credence to what the Catholic Church and European royalty had been indoctrinating them with years prior. Ordinary individuals now had access to such topics as scientific thought and political theory, both of which, upon publication, were considered blasphemy against religious beliefs.

This was the main reason some of the first book bans took place in the 15th century – or rather, book burning. As the war between Catholicism and the newly-founded Protestant church raged, Martin Luther’s new translation of the Bible was burnt in 1624, as it contradicted traditional Catholic dogma. Only a few years later, Galileo’s theories on the solar system were condemned by Catholic authorities. He was put on house arrest and forced to renounce his discoveries under the threat of torture.

Individual books were banned in various regions across the world for centuries later, due to them being what many intellectual authorities deemed at the time “morally inappropriate” or overly challenging of widely accepted beliefs. In the United States, Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain was said to be “‘rough… and inelegant,’” overall a bad influence on impressionable young minds. In the Soviet Union, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes was challenged because of its dealings with the occult.

The first notable widespread bannings (or again, burnings) of books, however, took place in Nazi Germany starting in 1933. Massive bonfires were hosted across the country to burn the literary works of Jews and communists, among others. Those works included the writing of scientists (sound familiar yet?) such as Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud, novelists such as Ernest Hemingway and Upton Sinclair – the latter of which was a key factor in why the U.S. established (much-needed) federal regulations on what we eat and drink in the early 1900s.

Though Nazi Germany is thankfully in the past, some may argue that its spirit lives on in America today through the suppression of literature. Since the beginning of the decade, there has been an uptick in the number of books banned in public and school libraries, according to the American Library Association. In 2023, 4,240 challenges towards unique titles were reported “the highest level ever documented” by the organization. Though the number of challenged titles dropped to 1,128 as of August 2024, it still “far exceed[s]” the data collected before 2020.

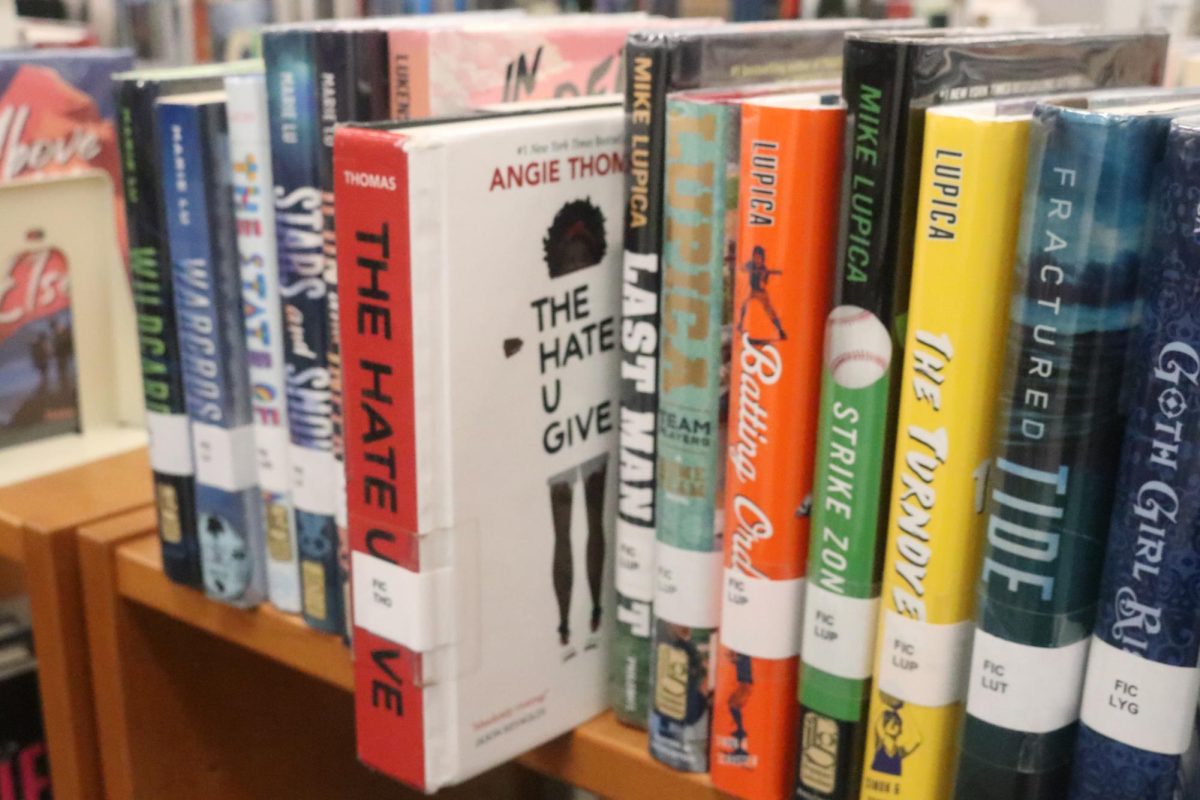

PEN America reports there have been almost 16,000 books banned in public schools all around the country since 2021, including repeated bannings of the same books in different cities and states. They claim this censorship has been spearheaded mainly by conservative groups, which target the discussion of race, sexuality, sexual violence, and/or LGBTQ+ orientation in such books. Other challenged topics can include drug use and addiction, suicide, nudity, profanity, violence, witchcraft, political bias, and many more.

The thousands of books banned throughout the 2023-2024 school year include classics such as The Color Purple by Alice Walker and The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood. Others are much newer, such as Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher and The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky. PEN America cites the most commonly banned book of the 2023-2024 school year as Nineteen Minutes by Jodi Picoult, with 98 bans around the nation. The bestselling novel tells the story of a school shooting and its impact on the small town in which it occurred.

According to the Stanford Daily, the reason so many books are being banned today stems from the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. “Due to at-home learning, parents had a greater insight into their children’s education,” Sanaya Robinson-Shah wrote, quoting book ban researcher Jennifer Wolf. “They often disapproved. Banning books is a convenient, easy and direct way for parents to have an influence [on what their students are reading].”

Using this data alone is enough to infer that there’s an agenda being pushed by those who wish to silence certain demographics, such as minority groups, females, trans or gay individuals, and others. Discussions of these “controversial” topics, however, such as race and school violence, are actually vital for both students and community members in bringing about awareness and positive change.

To use an example, the graphic novel Maus by Art Spiegelman was banned in a Tennessee School District at the beginning of 2022. Spiegelman’s work, which talks about the experiences of his Jewish parents while they lived in WWII-era Poland, was pulled out of its middle-grade school curriculum due to content the school board deemed inappropriate – eight curse words and a brief scene of nudity, according to PBS. “‘It shows people hanging, it shows them killing kids,’” PBS quoted board member Tony Allman. “‘Why does the educational system promote this kind of stuff? It is not wise or healthy.’”

In defense of the school board, books about the Holocaust usually don’t entail very happy subjects – but that’s just the point of such novels as Spiegelman’s. Conceptually, it is completely “wise” and “healthy.” Though uncomfortable, depressing, or even downright horrific at times, talking about these events informs younger people about necessary history. By teaching them these important lessons through something as accessible and as easily remembered as a graphic novel, it works to ensure that history never repeats itself.

Alas, repetition of history is exactly what is happening. Spiegelman regarded the decision as “‘Orwellian,’” essentially calling it something an authoritarian dictatorship would pull off. Upon learning about the situation via Twitter/X, the US Holocaust Museum tweeted, “‘[Maus] has played a vital role in educating about the Holocaust through sharing detailed and personal experiences of victims and survivors.’”

Besides that, nudity and profanity are unfortunately what many middle schoolers today are exposed to anyway. If the Internet wasn’t as widespread and influential as it is now, perhaps book banning would be a good technique to protect immature students from mature content. But mature content is only a tap away for many children, and some choose to tap in not knowing any better. There’s profanity and nudity in many TV shows whose target viewers are teenagers – Euphoria and Thirteen Reasons Why, for example. Porn is all across the web if you know where to look. People can deal drugs through Instagram DMs – just ask Texas Health and Human Services.

What’s the use of protecting kids from things they’re already familiar with? It boils down to the theory that some politicians, and others in positions of power, avoid acknowledging other races and important events. They fear it will impose blame on their generation for things done long in the past by their ancestors.

Take a look at books that cover slavery or racism. I have heard that many conservatives don’t want their children to believe that they should feel guilty about being white, on the account of white Southerners being slave owners or Jim Crow Law supporters in previous centuries.

The actions of previous generations are in the past, though. There’s nothing left to do but to move on. The only people who should feel guilty today are those who are still actively racist – and most of us aren’t, because there’s nothing that divides us now. We all have equal rights in the eyes of the law. There is no “us” and “them” anymore unless we continue to compare our differences.

There is no justification to remove or otherwise challenge books that discuss the experience of or pride in being members of a certain race or ethnic group. Portraying such books as being degenerative on the consciences of other races only breeds division, which is what everyone in the current age should strive to eliminate. After all, haven’t we learned from past mistakes?

Suppressing controversial information from young and impressionable minds is only a recipe for disaster. If conservative school districts continue to water down school library selections and classroom curriculum by giving students textbook definitions of difficult topics instead of more memorable depictions, they essentially make their children just like them. As these children grow up, they will never realize that banning books is not protection, but suppression.

Of course, there is always the argument (one mostly raised by conservatives) that parents should be at least vaguely aware of what their children are reading, especially if it’s provided by a school library or curriculum. Some parents do have valid concerns that should be addressed to some degree.

One of my teachers this year proposed a possible solution to the issue of filtering certain materials to individual students. It’s an opt-out system, one where parents can sign an agreement forbidding their students to read about certain topics in school library materials. Libraries around school districts can formulate a database with the names of students whose parents have opted them out of reading certain books. Something similar is already implemented in some English classrooms: if a book has material that may be deemed sensitive or inappropriate to the parents of some children, teachers can send a letter to parents to ensure they are informed.

There are limitations to that, however: parents and students can disagree about what the student is allowed to read, and this can obviously lead to conflict. Along with aspects of logistics, such as making sure everyone signs the form in the first place, this only shows that there’s no easy solution to book banning. Just as the problem itself isn’t black-and-white, a good solution needs to be multifaceted, and as intentional as possible.

Thankfully the future looks a little brighter for banned books in this state. WIS-10 reported recently that state representatives are looking to pass a law called the “Freedom to Read Protections and Respect for School Library Media Specialist Autonomy Act.” The legislation, if passed, would combat the removal of school library books around the state and protect the rights of students concerning easy access to reading materials. It would also increase transparency towards book challenges and protect librarians and media specialists from intimidation or harassment concerning book removals.

This means that it would be much harder for school boards and state lawmakers to ban books in the first place. As explained in the article, current state legislation regarding book challenges allows virtually anyone to challenge up to five books a month, meaning that the removal of the book depends on the opinion of only one person in the entire state. The Freedom to Read Act, however, would allow for a Material Review Committee to intercept such challenges. This would effectively stop most challenges before they deal any damage to school libraries, allowing students to continue reading freely.

If other states choose to pass similar laws, perhaps the freedom to read will live on across the nation. It is only through this, and advocacy from students, teachers, and librarians, that book banning will soon come to an end, hopefully for good.