Daniel Pearl High School in California was without a librarian. Adriana Chavira’s journalism students decided to discover why.

They pursued a story that discussed the vacancy left by the teachers that refused to get vaccinated, one of them being their school librarian.

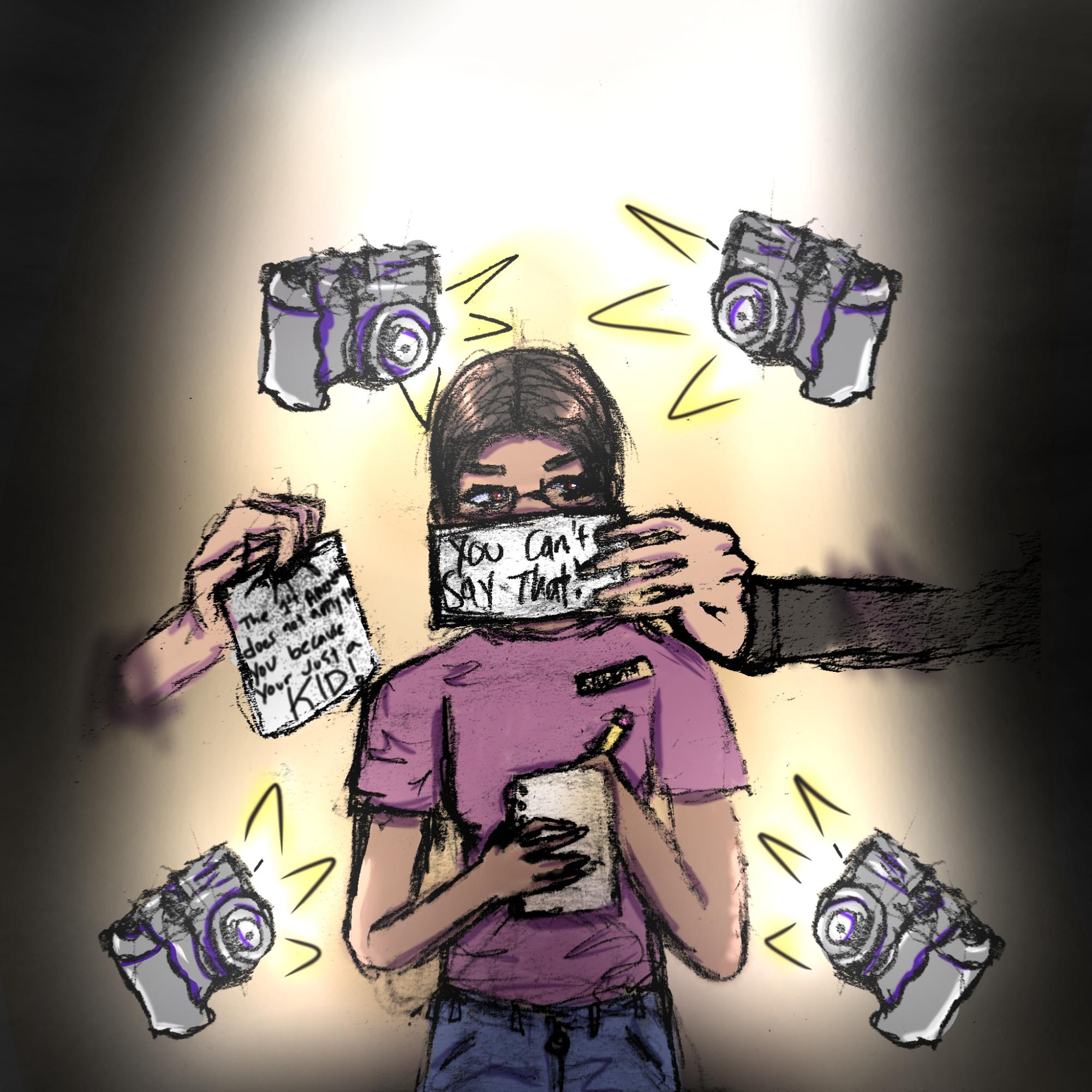

The article mentioned the librarian by name. After the story was published, the librarian directly contacted Chavira and asked that her name be taken out of the story. Chavira’s students refused to take her name out of the story, as they knew they had the right to report on the recent events that happened at their school. Several weeks later, administrators threatened Chavira with disciplinary action if she did not take out the name of the librarian.

In an interview with The Saber, Chavira said: “We just covered it like any other story. To me and the students we didn’t think it was going to be controversial. It wasn’t until a month after the story ran that we got notice to remove some information.”

Luckily, Chavira works in a New Voices state. New Voices legislation is put into place in order to protect and clearly define the first amendment and journalistic rights of students. Oftentimes, this includes the issues that arise from censorship. Such issues include bullying, harassment, and suppression of speech. Her state of California was the first state to have the New Voices legislation passed into state law.

What is New Voices?

The entire legislation of New Voices came from two Supreme Court cases. The first case, Tinker v. Des Moines, set the precedent for student press freedom. The case involved Mary Beth Tinker and a group of students that decided to wear black armbands to protest the war in Vietnam. The school board caught wind of this and passed a preemptive ban. So, when Mary Beth arrived at school on Dec 16. she was asked to remove her arm band and was then suspended. The students filed a lawsuit against the school district and the final decision ruled in favor of the students, stating that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gates”. This set the Tinker standard as one that advocated for the First Amendment rights of all students.

The Supreme Court case of Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier made Hazelwood become the precedent. Three high school journalists, including Kathy Kuhlmeier, sued their school district after the principal at Hazelwood East High School, Robert E. Reynolds, removed articles from a pending issue of Spectrum, the school’s newspaper. Although the students won their case in the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the school district. This set a precedent, that schools may restrict what is published in student newspapers. The current national standard is the Hazelwood standard.

New Voices legislation aims to revert back to the Tinker standard, which allows students to freely discuss potentially controversial topics as long as they don’t cause school disruption. Most states currently fall under the Hazelwood standard which gives school administrators power to censor speech going off of vague criteria. Currently, there are 18 states that have New Voices passed within their state legislature. These laws help protect student journalists and advisers when issues like Chavira’s come up. This does not mean that students have the right to publish whatever they feel like. There are five major points that New Voices legislation does not protect students from.

According to Grayson Marlow, a correspondent from the Student Press Law Center (SPLC), this includes “libelous slander, unwarranted invasions of privacy, obscene content, violations of federal or state law, and content that incites students to create a clear and present danger in the commission of an unlawful act.” The SPLC is the main organization that leads the New Voices movement, and provides free legal help for other journalistic issues.

“These bills [referring to New Voices] restore first amendment rights to student journalists, who at the moment have less rights than their fellow students,” Marlow said.

New Voices bills gives students the right to discuss controversial topics and to report on them as though they are professional journalists.

“The New Voices Legislation would prevent a situation where a principal can be a dictator of his own school, and decide what people get to know and don’t get to know, and who gets to speak and who doesn’t,” said Elizabeth Swanne, a veteran journalism teacher at Nation Ford High School in Fort Mill.

Self Censorship

Since California already had New Voices implemented into their state legislature, Chavira knew that her students were doing the right thing by reporting on newsworthy events. Instead of dwelling on the possible consequences she may face, Chavira focused on another problem that can arise when student’s face censorship.

“I made sure the student’s knew not to self censor,” Chavira said.

Self censorship is the act of censoring one self in order to avoid harsh criticism or judgment. It happens when journalists fear of the possibility of being censored, which makes the individual question even writing a story in the first place. This can lead to the under-reporting or avoidance of serious issues.

“We often say that censorship breeds more censorship. If a student is censored they will then self censor and not even bring up topics. Some will even choose to leave their journalism programs,” Marlow said.

New Voices in action

Chavira’s situation is not a new concept for California. Sometimes, these cases can become lawsuits against principals and administrative teams. Two California students and an adviser at Mountain View High School sued their district and administration; accusing them of ‘bullying’ the student newspaper staff to ‘save face’ as they had cut a journalism class and removed the adviser. Former reporter Hayes Duenow and former advisor Carla Gomez allegedly state that the actions were due to an investigative article about student-on-student sexual harassment at the school. The decision for the case has not yet been made.

“It was frustrating because I knew that the law was in my corner but the district still kept at it.” Chavira said.

Leslie Dennis is a current journalism teacher at RNE, who also has a background in directing organizations for journalism education at the University of South Carolina. She shares her standpoint on the movement in South Carolina.

“There hasn’t been any official movement in South Carolina; I do know that there are passionate advisors that would like to see New Voices passed in the state,” Leslie Dennis said.

There are many ways that information can be spread to push the New Voices movement. Here are some examples of what you can do: